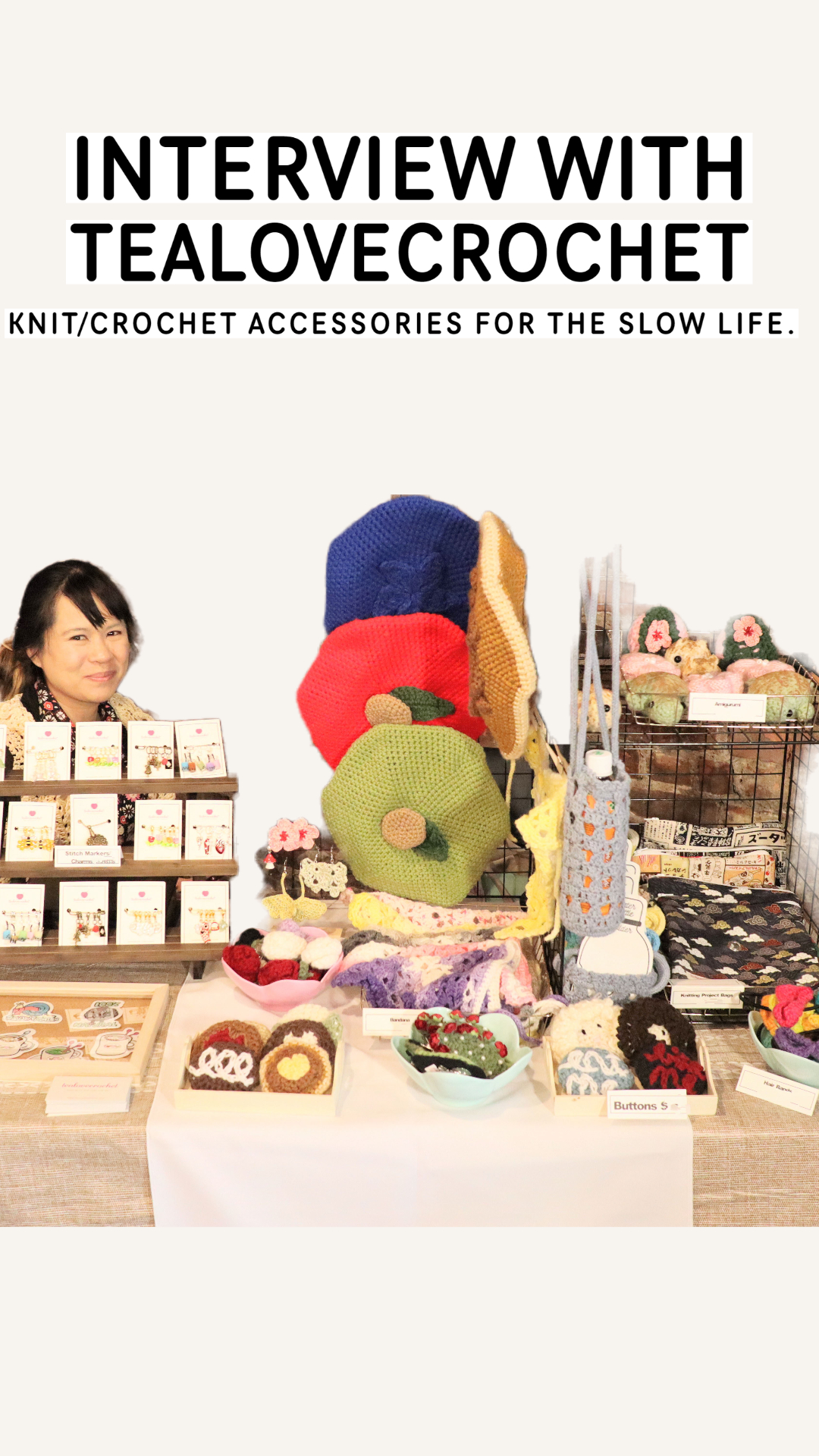

We spoke with the creator, Mai, about her brand’s beginnings, her experiences at markets, and her vision for the future.

Based in New York, Kazaria3 is a handmade hat brand that transforms vintage kimono fabrics and obi textiles into modern, wearable pieces. What began as a self-taught creative journey has now grown into a beloved brand supported by many repeat customers.

Q/What is the meaning behind the name “Kazaria3”?

I wanted a name that sounded Japanese, so the idea of okazariya-san came to mind first.

I live in an area called Astoria, and because the sound is similar, I combined “okazariya (Kazariya)” with “Astoria,” which became the brand name Kazaria3.

Q/How did you start making hats?

During the pandemic, masks were in high demand, so I started making them.

Originally, I made jewelry accessories, but as I shifted to making fabric items like masks, I began thinking, “I want to try making other pieces too,” which led me to create hats.

Since hats received especially positive reactions, they eventually became the center of my current lineup.

Q/What items do you currently make?

I currently make bucket hats, caps, ear-flap caps, and winter hunting-style hats.

Until last year, I also made berets, but now I focus on seasonal items. Bucket hats are especially popular overseas. They’re easy to wear casually, and I find it interesting how the same pattern can feel more suitable for a bucket hat rather than a cap depending on the customer.

Q/Do you offer custom orders?

I try my best to meet detailed requests such as size adjustments and changes to the brim length.

Because head sizes vary widely overseas—some people need larger sizes, while others are petite and prefer much smaller ones—offering custom options is very important when selling internationally.

Q/How did you learn your sewing and hat-making skills?

I am completely self-taught.

Back in language school, several of my friends were studying fashion, and their influence encouraged me to try making simple clothes on my own.

After a while, my sister asked me to make her wedding dress. Honestly, I thought, “There’s no way I can make that,” but I researched on YouTube, experimented with combining patterns, and somehow completed one dress. My sister was happy with it, and I was very happy too.

Through this experience, I gained the confidence that “if I try, I can do it”, which connects directly to the work I do today.

Q/Why did you switch from other fabrics to kimono textiles?

In the beginning, I used fabrics I had on hand, such as African prints. However, when a customer asked me, “Why are you using African fabrics?”, I realized that I was working with materials that did not reflect my own cultural roots.

Since then, I wanted to express myself using materials that are connected to Japanese culture and background, which led me to start working with kimono fabrics.

Q/How do you source kimono fabrics and obi textiles?

I used to purchase them at kimono and textile exhibitions held in New York.

Recently, when I return to Japan, I visit vintage shops in places like Kyoto and select fabrics by hand. I sometimes buy online as well, but I prefer choosing materials while checking the texture and colors in person whenever possible.

Q/What do you focus on when selecting materials or designing?

I mainly use obi fabrics for bucket hats.

Bright colors and bold patterns—such as orange or gold—tend to be popular in the U.S.

On the other hand, fabrics that make people say “Is this really kimono fabric?”—designs that don’t look too traditionally Japanese—are also popular.

Blue tones are frequently chosen, and motifs reminiscent of anime, like checkered patterns, often attract interest.

When selecting materials or patterns, I prioritize my own intuition. I choose fabrics that I find “cute” or “interesting,” and try to bring out their charm in the finished pieces.

Q/How do you sell your hats, and what has your market experience been like?

I don’t use my online shop very much; instead, I mainly participate in pop-up events.

I also receive orders through Instagram.

I have participated in more than 20 markets so far. The market I attend most often is the one organized by Niji at Japan Village.

Many visitors are interested in Japanese culture, and the number of repeat customers has increased.

Each event has a different audience and atmosphere, so the reactions vary greatly. Some markets suit my work very well, while others don’t match in terms of price range or vibe. There are many things you only learn by actually participating, and I feel that each experience leads to valuable insights.

Q/Do you have any memorable customer stories?

At Japan Village, a customer I met once returned to another event and purchased more hats. Some customers have bought multiple hats over time, which I’m very grateful for.

I also once received an order—through an event organizer—to make a hat as a gift for Nicola Formichetti, known as Lady Gaga’s stylist. He even gave permission for me to use the photo, and the unexpected connection made me incredibly happy and left a strong impression on me.

Q/What goals do you have for the future?

I want to increase the use of recycled vintage kimono fabrics and eventually create original patchwork textiles by combining leftover fabric scraps.

Hat-making naturally produces small pieces of fabric, and I don’t want to waste materials I feel attached to. I have already begun experimenting with patchwork. It takes time, but I’m working steadily so I can make use of these precious scraps.